Renaissance Athlete

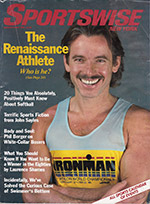

The Renaissance Athlete

Sportswise New York, March/April 1948

By Paul Good

Michael Kasser is a shortish, 155-pound, 43-year-old “Iron Man” who ran the London Marathon last April 18, jetted the Atlantic that night, and ran the Boston Marathon the next day, averaging three hours a race.

He has goat-footed down a snowy Nevada trail in the pre-dawn dark 6,000 feet above sea level to finish the Western States 100-Mile Endurance run. He has also swum in the sea off Hawaii watching dolphins cavort beneath him during an Ironman Triathlon. And in the same Tri he biked more than a hundred miles through a volcanic landscape baked hotter than the sunny side of the moon.

He’s a man with more degrees than a thermometer, including a B.S from MIT, an M.B.A. from Harvard, and a Ph.D. from the University of Grenoble. When he isn’t giving life a run for its money, Kasser is publishing books written by the likes of poet Allen Ginsberg and “druggist” William Burroughs. He also produces high-quality off-Broadway plays, studies acting and writes songs while he puts in three hours a day learning to play the piano.

And in the dramatic SoHo apartment he shares with dishy ultra runner Beth Sedgwick, Kasser collects pre-Columbian pottery, sleekly erotic modern metal abstract sculpture and Goya reproductions. Oh yes, and he also collects tidy bundles of U.S. dollars as a venture (he likes to call it “adventure”) capitalist specializing in buying into companies ripe for takeovers and betting that the stock price will go up. He is unabashedly into Cash, along with Culture and Conditioning.

What makes Mikey run?

The reasons—as we shall see—are multiple and varied. But one thing’s certain: In an age when the term “Renaissance Man” is applied to any guy who holds down an office job, plays ping pong and the kazoo, and maybe writes greeting card verse for his Mommy on her birthday, Kasser can lay some legitimate claim to the title. Yet only ten years ago, he smoked a pack-a-day, resembled Tweedledum—or dee—or both—at 182 pounds, and limited his athletics to running out of steam.

“If I can do it,” says the laid-back entrepreneur sipping a beer one afternoon in his brick-walled living room which is the size of a couple squash courts., “anybody can. Look, my first marathon time was 5:30 back in 1974. My best was 2:53 last year. When I applied for my first triathlon in the Groton, Conn,. Sri Chimnoy, I didn’t even own a bike and I swam maybe two or three times a year in a pool.

“Two years later, I was in Hawaii doing the Ironman — 112 miles on the bike, 2.4 mile swim in the Kona surf and a 26.2 mile run. And you can see I’m not built like Scott Tinley or Conrad Will.”

However Dorian Grey-youthful Kasser appears, he is not in the same physical class with those premier athletes. He’s trim, dark-haired, with a dashing moustache and lively brown eyes. He cheats upward on his personal sports resume when he lists himself at 5-8. His arms, hands and feet are small; the overall impression is a Joel Grey wiriness, even delicacy.

Your average New York City mugger would probably consider Kasser just the “right sort.” Wrong. He has developed, through marathons, ultras and tri’s, the kind of physical and mental toughness that may just make him the best 43-year-old athlete in town.

How did Kasser go from a roly-poly little slewfoot to the svelte fleetfoot he is today? Like most accomplishments in life, it wasn’t easy.

While he sits at his Kurtzman baby grand playing the old torch song, “I Can’t Get it Started” (it could double as a marathoner’s lament), a visitor is attracted to the room’s memorabilia. There’s a plaque for first place overall in the New York City Road Runners Club (NYRRC) 1983 Knickerbocker 60K. No clue there. That’s Beth’s plaque; she’s currently gunning for the women’s 100-mile ultra record.

On another wall, there is a handsome collage mixing painted running scenes with photographs of Kasser and friends. Done in oils by artist Erica King, the collage guides the eye to various milestones in the Kasser career, including a Certificate of Achievement from Mayor Ed Koch. It also has the official stamp on Kasser’s first marathon, and it begins the story of how and why running changed his life…

It’s the early 70s and Mike is married to an actress. He’s running his own sawmill in upstate New York and life is pretty good for this Hungarian-born son of a chemical engineer who came to America in 1949. In college, by his own estimate, Kasser was a totally average athlete who finally made the MIT tennis team as a senior after sitting out his sophomore and junior years because of rheumatic fever.

He had tried after college working for others in chemical engineering and finance, and then decided to be his own man by buying the sawmill. He makes it a success, the money is coming in, but his gut is stretching out. The old story of “getting and spending we lay waste to our powers.”

Kasser quits smoking but not eating. He rolls his 182 pounds onto the squash court a few times a week and starts to jog—and jiggle. In periodic trips to New York, he runs in central park, barely staying even with the horse-drawn carriages. One day, still hefty, he runs a loop of the park with some marathoners. That leads him to join the NYRRC and to train haphazardly.

He is doing 30 miles on a very good week when he enters the ’74 New York City Marathon. He is an unpleasingly plump contestant. He thinks he can do the course in 3:30. Haw!

“It was a hot, muggy day,” he recalls. “At approximately ten miles we were hit by a rainstorm that lasted over an hour. At first, the cooling effect was welcome, but after mile 14 I was ready to quit—cold, tired, alone.”

“Running past the NYAC, I stopped. That was it. I walked off the course towards the club, the thoughts of a sauna and a beer were overpowering. But something made me turn back as I waited for the lights to change at 59th and Seventh. When would I ever do this again, I thought. Never! The feeling of advent sure, the thought of having a great story to tell my friends and eventually my kids, got me back on the course…”

The rest of the race, which he finished after everyone but the loyal timekeepers had gone home, was agony. But Kasser was back on course in more ways than one.

His 5:30 finish was achieved in a kind of pain and loneliness that only the inept long distance runner knows. After two days in a recuperative bed, he vowed, “Never again.” A desultory year followed. He hated the way he looked and felt. So in 1976, Michael Kasser—still in sloppy shape—returned to run the NYC Marathon in 4:12. Why?

“I was a desperate man,” he says. “I was grabbing onto the idea of the marathon as both a challenge and a pledge to myself. It was a symbol of what I was and what I had to become to live with myself.”

Kasser didn’t know it then, but just a few years down the line, running would help him through a worse time and draw him inevitably toward the most severe challenges in modern athletic competition.

He did two marathons in 1977, three in 1978. The weight was coming off, the times dropping down below 5:00, below 4:00, the body was picking up new rhythms. Now, he was back in New York City, and the mill he had bought for $900,000 sold for $6 million.

Then, in 1979, Kasser’s emotional life ran off the track when his wife divorced him. He doesn’t go into details as he sits in that lavish SoHo living room that radiates the sweet glow of success. He doesn’t have to explain as he says: “At that point, running became like an escape. I needed a place to park my soul, some safe place to figure out what’s next. I don’t mean that it was all laid out neatly in my mind at the time. But you can think of it as a therapeutic hobby, a way to get lost and at the same time meet other runners who became sharers with me. It helped the loneliness.”

Kasser seemed to be running away from himself and toward something at the same time. He was crowding 40 now, often a traumatic age for men as well as for women. Running was an end in itself but it was also an ego trip. He wanted to stay young and sexy. His business deals were often conducted at the lunch and dinner table where he liked to eat well and drink in a socially moderate but calorically high style. Training to run, he could easily burn off 6,000 calories a day, holding middle age at a distance. He had a crazy notion to do a marathon a week for 52 straight weeks.

“I decided that was obsessive,” he says. “But at the start of 1980, I did five marathons in six weeks.”

He also did his first back-to-back marathons in 1981. He ran first in Phoenix on Dec. 7, then in New Jersey on Dec. 8, and celebrated his 40th birthday the following day. It was the kind of freakish performance that he was to repeat in the 1983 London-Boston marathons that makes you wonder about his motivations. But as you get to probe the man, the more you feel that it was a private need that impelled him rather than a public display (and isn’t it that way with the majority of runners?).

“At one of those 1980 marathons,” Kasser says, “I saw a guy at the finish line in a T-shirt printed with the announcement that the Sri Chimnoy Triathlon—he was a kind of guru—was coming up in Groton, Conn. There was a mile swim, a 25-mile bike, and a ten-mile run. I decided to do the damn thing, as an adventure. There was no publicity ego-stroking thing then or now. The newspapers hardly noticed. An adventure was all it was.”

“I bought a Raleigh 12-speed and started swimming at the NYAC pool. And I finished 30th out of 200. If I had been a few months older, I would have placed second in the 40-and-over class. I said to myself, ‘Hey, here’s something I may be competitive at.’”

That something was the growing sport of triathloning; there were 1,100 triathlons in 26 countries last year. One factor attracting Kasser and his fellow Tri-harders is the possibility of placing in one of the multiple age-group categories, such as 18-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39 and so on. This peer-group competition hones the edge of desire for participants who must have a “winner” mentality in the first place if they are to offer their bodies to the test.

Even so, Kasser knew about few of the nuances when, in 1982, he entered the grandaddy of all triathlon events, the Hawaii Ironman. “There were no real training guides,” he says. “So in 1981 I trained myself on ultras like a Connecticut 60K and a 100K in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. I was feeling very good about myself. I thought I could do Hawaii, especially that fall when I did a 2:57 in the New York Marathon.”

Business permitted him to get to Hawaii early and he poured it on in training, doing 300 miles a week on the bike, swimming eight miles and running 50, getting acclimated to the heat and sun. Kasser insists that triathloning is an Everyman’s sport, despite the training time and travel money required.

“The people doing it are wonderful,” he explains. “And talk about a classless society, that’s it. The first time in Hawaii I found jocks who trained year-round but didn’t have a dime, others who had a certain limited amount of free time and money. It’s a question of priorities. And as far as physical demands go, for anyone who has done a marathon, it’s not out of reach.”

Competing against a thousand others in Hawaii, Kasser’s first goal was to complete the course, his second to do it in 13 hours. Swimming was his weakest event and he came out of the water about 300th. “But after the bike I was 175th,” he says. “The course was a monster, an animal. But I had a tremendous bike ride and finally came in 117th overall with a time of 12 hours. I learned a lot about mental toughness in that Ironman. Physical conditioning, of course, is vital. But ultimately, you win or lose, finish or drop out, in your head.”

In the next Ironman, Kasser placed 85th overall and second in the Masters division. The more he raced and trained, the more life opened other doors to him. He satisfied a long-time urge to study the piano, attending the unique Dalcroze School in New York that—appropriately enough for a triathlete—emphasizes the merging of body movements with what’s happening on the keyboard. Soon he was analyzing Chopin and Hayden along with acquiring the chords to “Melancholy Baby.”

At the same time, he began studying acting at New York’s renowned “New School” and producing off-Broadway plays with playwrights who had off-Broadway credentials. Writers like David Mamet and Paul Zindell, who won a 1971 Pulitzer for his “The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds.” Kasser started his own publishing company titled after a game he never played—Full Court Press; it produced a collection of William Burroughs’ letters to Allen Ginsberg and a hitherto unpublished book of Ginsberg’s earlier works.

Kasser doesn’t claim that running propelled him into all these new directions. But, he says, “It provided a balance in my life. One thing that happens in New York is you get too involved with the head, the intellect, the creative or financial side of life. You come to scorn the physical. But we are born to both things and if you deny one, you deprive yourself.”

Last October, he felt that he was ready to murder the Ironman event. He had broken the Master’s record in the Sri Chimnoy, had run a hundred miles in and around Shea Stadium finishing 16th, had puffed his way to the top of the Empire State Building in a vertical race, and had finished a very respectable 48th out of 500 participants in the Mighty Hamptons Triathlon. Everything was going well.

That is, until he began training in Hawaii. Ten days before the Ironman, he had a bad bike spill. A doctor spent three hours picking black coral from his hide. He ached, lost sleep, and even though he was in the best shape of his life, Kasser came apart in the race.

His concentration deserted him, testimony for the need for mind and body to function together in personal events that can’t depend on teammates or the lure of gold to see you through.

“The first miles into the biking I was really hammering,” he remembers. “Then the wind hit in the lava fields and I lost my intensity. Same wind for other people, no excuses. People I had passed in other races were passing me. That had never happened before. At mile 85, some creep had sprinkled tacks on the road and we all came down with flats. I took too long to change. Then the run. I always feel terrible at the start of a triathlon run. I know that I won’t make it. I feel bad for eight miles, better for the next ten, then bad for the remainder. What kept me going was guys my age a few miles ahead. I knew I could beat them. But I finished totally dead, my worst time at 12:00.56, and all the masseurs rubbing me back to life and the bananas with their carbohydrates and potassium to nourish me didn’t help.”

He remembers going back to the local restaurants and pigging out. But when Kasser projects what his life will be like in running, it isn’t based on the hog style of long ago.

“Basically we’re animals,” he says. “We have to use our bodies for what we are put on earth for. For me, it’s a word called “adventuresomeness.” Nowadays, Lindblad Tours can take you to the North or South Pole. The only unexpected place is ourselves. People are finding that we are pretty damn okay. So we run.”

So we run.